Change is the end result of all true learning.

- Leo Buscaglia

For decades, the Taliban have worked to stop girls from being educated. Taliban gunmen shot fifteen-year-old Malala Yousafzai in the head to silence her as an advocate of girl’s education and a favorite Taliban tactic has been to throw acid in the faces of female students so they’re too terrorized to go to school1.

Why this horrific campaign against girls? Well, whatever else they are, the Taliban are not dummies. They know that learning leads to change, and a more educated female population would almost certainly not accept the Taliban’s repressive rules. So it’s a calculus, that the costs of scarring girls for life or killing them are less than the potential costs of girls being educated because the Taliban want things to stay the same, namely with them in charge.

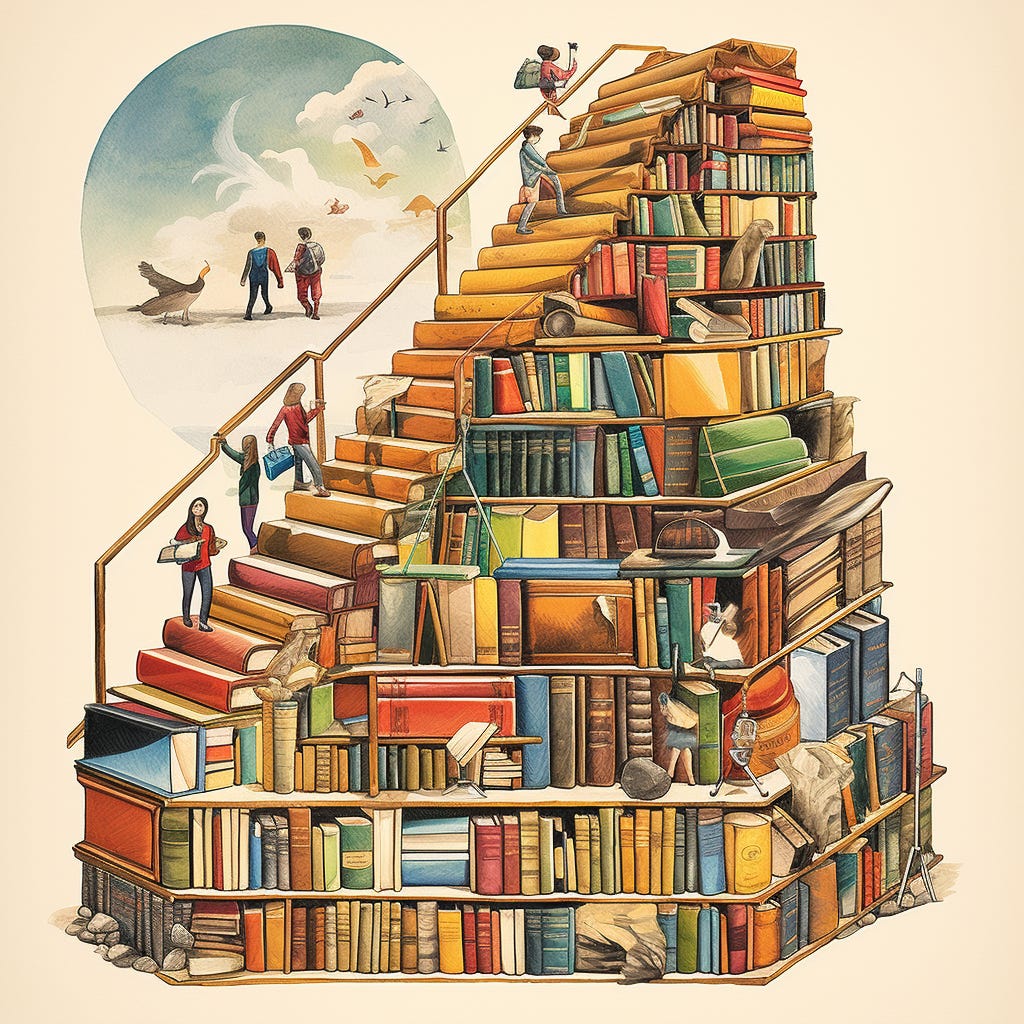

But the world doesn’t stay the same, and for us to adapt to a changing world, for us to figure out where we can best be of service, we need to be constantly learning. This is particularly important in an era of climate change, when many solutions are either works in progress or yet to be developed. Unfortunately, many people stop learning. Or, they forget how. They get comfortable with what works, they achieve homeostasis, and before they know it, ten or twenty years have gone by and they’re doing the same thing they’ve always done except it’s not working so well anymore.

Organizations stop learning, too, even ones with formal lessons learned programs. These programs often don’t go anywhere because key people are too busy to take part, or not enough time is set aside, or lessons aren’t widely shared. Each Afghanistan Task Force I was part of would complete a report on Lessons Learned. And, those reports would usually go to some central depository where they’d rarely be read. Like most things, learning takes time and effort. Perhaps the most profitable activity I’ve done since pursuing writing has been to take course after course, and read book after book on the subject. In other words, I dedicated time to learning.

To be done effectively, learning should be tied to observations about the evolving environment and the effects of our own actions, seeking to understand how our current situation might have changed, and how we might need to adjust our own actions accordingly. Remember, learning is a process, and that process is often one of trial-and-error since we often won’t get things right the first time we try something new. When I served in Special Operations, we used four questions to guide our learning process: What are we doing that’s working and that we need to keep doing? What are we doing that’s not working and that we need to improve? What are we not doing that we should be? What are we doing that’s unnecessary?

Learning isn’t about changing our goals; it’s about finding better ways to accomplish them. As a writer, I experiment with different literary techniques and structures so I can expand my tool box and improve because that helps me serve people better through more effective communication. As people aiming to serve others, that experimentation might be about finding the best place for us to serve, or discovering where we could add the most value in helping others prepare for climate change.

As a last example, after being shot, Malala didn’t give up fighting to ensure every girl has the opportunity to get an education. Instead, she learned how to pursue that goal more effectively, such as by establishing the Malala Fund, whose mission is to work, “…for a world where every girl can learn and lead2.” And if Malala can commit to learning under threat from the Taliban, if she can keep that commitment after being shot and displaced from her Swat Valley home, then surely, we can too.

Shaan Khan, ‘Pakistani Taliban target female students with acid attack,’ CNN, Saturday, November 3, 2012, https://www.cnn.com/2012/11/03/world/asia/pakistan-acid-attack/index.html, accessed 30 Sep 2021.

Malala Fund, ‘About Malala Fund,’ malala.org, https://malala.org/about?sc=header, accessed 30 Sep 2021.